In this credit rating methodology[1], we explain our general approach to assessing credit risk for financial institutions including banks, finance companies and securities firms, and to assigning issuer-level and debt instrument-level ratings in this sector in Vietnam[2].

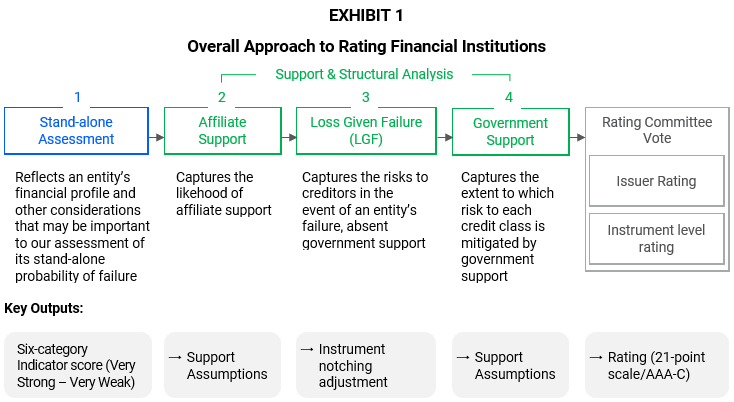

As part of our credit analysis in this sector, we establish a stand-alone assessment for a financial institution entity. A stand-alone assessment reflects our opinion of the entity’s intrinsic credit strength, absent any support from an affiliate or government, relative to other financial institutions in Vietnam, and the company’s likelihood of requiring support to avoid a default. We then incorporate affiliate support, which reflects our opinion of the entity’s ability to pay its debt and debt instruments given support from an affiliate, and finally we include government support, that reflects our opinion on the likelihood of support to be provided by the government in an event of stress.

We discuss the qualitative and quantitative factors that are likely to affect rating outcomes in these sectors. We also discuss other considerations, which are factors for which the credit importance may vary widely among financial institutions or may be important only under certain circumstances or for a subset of entities. We discuss our approach to assessing the potential for affiliate support and the potential for government support. Furthermore, since credit ratings are forward- looking, we often incorporate directional views of risks and mitigants in a qualitative way. We determine debt instrument credit rating given our estimation of loss given a failure of a financial institution.

Our presentation of this credit rating methodology proceeds with a discussion of (i) the stand-alone assessment factors and other considerations; (ii) assessing affiliate support; (iii) loss given failure notching guidance; (iv) assessing government support and intervention; (v) assigning issuer-level and debt instrument-level ratings; and (vi) general limitations of the credit rating methodology

Source: VIS Rating

In this section, we explain our general approach for quantitative factors used to assess credit quality for our stand-alone assessment. We describe why each is meaningful as an indicator of a financial institution’s stand-alone assessment. We consider factors related to a financial institution’s business model and financial profile. For each factor, we will assess based on an eight-category scale: Very Strong, Strong, Above-Average, Average, Below-Average, Weak, Very Weak and Extremely Weak. In the following section we assess other considerations to arrive at the stand-alone assessment. Our assessments are forward-looking and reflect our expectations for future financial and operating performance. However, historical results can help to understand patterns and trends of an entity’s performance as well as for peer comparisons.

Financial ratios, unless otherwise indicated, are typically calculated based on an annual or 12-month period. However, the ratios can be assessed using various time periods. For example, credit rating councils may find it analytically useful to examine both historical and expected future performance for periods of several years or more which may be impacted by factors such as expected changes in macroeconomic conditions, market dynamics, business environment, as well as company-specific factors such as corporate strategy and governance, key personnel risks etc. In the financial metrics we consider how well financial reporting mirrors economic reality. Where we believe the financial reporting does not capture the economic reality sufficiently, we may make analytic adjustments to metrics derived from financial statements to facilitate our analysis.

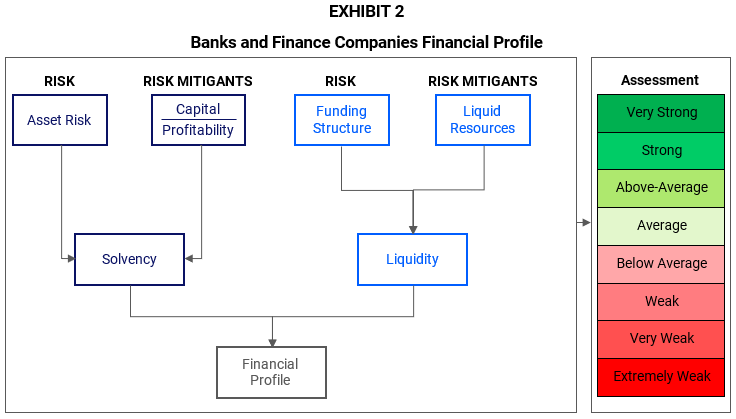

Our analysis of a bank’s or finance company’s financial profile incorporates key considerations on solvency and liquidity, which are important indicators of its exposure to risk and its capacity to absorb losses.

Source: VIS Rating

Solvency incorporates a bank’s or finance company’s overall asset risk (exposure to credit, market, operational and related risks) and the extent to which its capital and earnings create the capacity to absorb losses. The liquidity factor assesses a bank’s or finance company’s funding structure and its liquid resources.

Solvency and liquidity are related. Stronger capitalization increases the capacity to absorb losses and the confidence of counterparties, and reduces liquidity risks. Greater liquid assets indirectly enhance solvency because they imply that an entity is less likely to need to sell illiquid assets at a loss in the event of a funding problem.

Solvency is indicated by a bank’s or finance company’s asset risk relative to its loss-absorbing capacity. Mitigants to asset risk are a bank’s or finance company’s capital and reserves, which are designed to absorb losses, and its earnings capacity.

Asset quality is fundamental to the determination of the creditworthiness of a bank or finance company, as it reflects the strength of its business franchise, risk appetite and management’s ability to manage risks effectively.

Banks typically have high leverage, and a small deterioration in asset value tends to have a large effect on solvency. Finance companies often operate in niche sectors that are intrinsically higher risk and that can be vulnerable to changing market sentiment, irrespective of expected asset quality performance. Asset quality deterioration in a cyclical downturn can be more pronounced for a finance company than for more diversified lenders, such as banks.

In Vietnam, loan portfolios are generally the largest component of a bank’s and finance company’s balance sheet. Therefore, loan quality is considered a key component in determining the creditworthiness of banks and finance companies. Among multiple financial metrics that we use to assess loan quality, we analyze the extent of problem loans and the level of loan loss reserves.

How We Assess It

In assessing a bank’s or finance company’s asset risk, we use the ratio of problem loans to gross loans and the ratio of loan loss reserves to problem loans.

PROBLEM LOAN RATIO:

As loan quality deteriorates, the problem loan ratio rises, signaling potential problems such as credit losses and consequent pressure on solvency, earnings, and equity, all of which are capital buffers that protect bondholders.

The numerator of the ratio is total problem loans. We define problem loans as loans that are classified as nonperforming and/or overdue for more than 90 days, and other loan and assets that are not classified as nonperforming, but we view to have weak credit quality and relatively higher likelihood of future impairments. The denominator is gross loans. For banks and finance companies, gross loans include loans and leases to customers. We exclude allowances for loan losses and other deductions.

In assessing historical metrics, we typically calculate or estimate the ratio using the weaker of the most recent three-year average and the latest annual or 12-month figure.

LOAN LOSS RESERVE RATIO:

Strong loan loss reserve coverage may mitigate the risk of problem loans, while low levels of coverage may expose banks or finance companies to the risk of volatility in provisioning and to unexpected losses that erode capital. A lower ratio typically indicates worsening loan quality and signals that the bank or finance company has fewer reserves to cover problem loans, or that problem loans are rising faster than loan loss reserves.

However, ratios may not always be comparable without also considering the extent to which the portfolio benefits from collateral. Entities with a loan book that is mostly backed by collateral are likely to have lower ratios due to higher expected recoveries.

The numerator is the loan loss reserves, and the denominator is total problem loans.

In assessing historical metrics, we typically calculate or estimate the ratio using the weaker of the most recent three-year average and the latest annual or 12-month figure.

To formulate our forward-looking expectation of asset quality performance, we consider other factors and leading indicators of asset quality performance including historical loan growth and loss performance, management strategy and risk appetite, credit concentration, related-party lending, other non-lending activities that pose credit and financial risks, risk management and controls, etc.

Capital adequacy is a key element in a bank’s or finance company’s ability to mitigate risk and absorb losses, including write-downs or the impact of a crisis that causes a dislocation in financial markets.

How We Assess It

We assess the level of tangible common equity (“TCE”) to risk-weighted assets (“RWA”). We view this ratio as a predictive indicator of a bank or finance company failure. Our TCE measure comprises mainly Tier 1 capital under local regulations, which we regard as higher quality capital that will help to absorb losses on a going-concern basis. Where RWA figures are unavailable, we will consider using total tangible assets as the denominator.

We will also consider other factors including internal capital generation capacity, management growth strategy and risk appetite, dividend policy, adequacy of capital level for risk profile, access to fresh capital and capital buffer available to absorb losses in stress scenarios, etc.

Profitability is core to a bank’s or finance company’s ability to support creditor obligations, generate capital and fund growth. Core or recurring profitability is the first line of defense to absorb credit related losses and losses stemming from market, operational and business risk. A high degree of overall stable earnings from diverse sources can help a bank or finance company absorb shocks that may arise from some business lines.

How We Assess It

In assessing a bank’s or finance company’s profitability, we use the ratio of net income to tangible assets. We also assess the quality of income by comparing income contribution by core business lines, risk-adjusted profitability of key business lines, accounting and provisioning policies, management track record to scale and manage costs, diversify and grow new recurring income streams.

In assessing historical metrics, we typically calculate or estimate the historical ratio using the weaker of the most recent three-year average and the latest annual or 12-month figure.

A bank’s or finance company’s ability to access liquidity on a recurring basis is an essential component of its operating model. Strong liquidity is essential for an entity to remain adequately funded during difficult periods in credit markets.

Liquidity risk for banks and finance companies often arises from the use of less reliable funding, typically wholesale funding sourced from institutional investors, which tends to be more confidence-sensitive and volatile than retail deposits. Mitigants to diminished market access include the bank’s or finance company’s liquid asset reserves and effective asset-liability matching.

At times, due to idiosyncratic or broader, systemic concerns, banks and finance companies can suffer restricted access to funding markets. This can result in a higher cost of funding, a shortening duration of liabilities or a need to sell assets ahead of maturity, potentially resulting in losses and reducing capital.

A bank’s or finance company’s funding structure has a strong bearing on its credit quality because some funding sources are less reliable than others. Diversity in a bank’s or finance company’s funding across a variety of sources can lead to greater overall stability.

Banks in Vietnam are primarily funded by retail and institutional customer deposits. In contrast, most finance companies tend to rely heavily, if not, entirely on confidence-sensitive wholesale funding, which increases their vulnerability to external shocks.

How We Assess It

In assessing a bank’s funding structure, we analyze the strength and quality of its deposit franchise by using the ratio of core low-cost customer deposits to gross loans. The numerator comprises current account and savings account deposits. The denominator comprises total gross loans to customers.

A higher ratio generally indicates a bank’s ability to attract more stable funds to support its main lending business and a superior funding structure. In addition, we consider other factors such as depositor concentration, funding support from affiliates, reliance on short-term market funds for core lending activities, diversification and reliability of its market funding counterparties, extent of funding gaps and refinancing risks.

For finance companies, we consider the diversity of its fund providers, the entity’s track record in placing debt across a wide range of maturities, funding support from its parent and/or affiliates and its access to unsecured, committed bank lines for contingency funding. To assess the relative vulnerabilities brought about by their wholesale funding profiles and their ability to access liquidity on a recurring basis and flexibility to deal with market events and stress, we focus on analyzing their cash flow and liquidity (discussed in the next section).

A bank’s or finance company’s liquidity profile considers the composition of its assets. Liquid resources are enhanced when a bank or finance company has a high level of high-quality liquid assets that can be readily sold or pledged for cash in private markets in response to its funding needs, which are driven by the firm’s own business as well as market conditions and counterparty behavior.

Finance companies have a recurring need to access the funding markets to sustain their asset origination activities. Because wholesale funding is sometimes unreliable, a liquidity crisis, whether company-specific or precipitated by a market event, can have a profound effect on even the strongest finance company, whereas strong liquidity can help an institution remain adequately funded during difficult times.

How We Assess It

For banks, we use the ratio of liquid banking assets less market funds to tangible banking assets. The numerator, liquid banking assets include available and unrestricted cash plus amounts due from other credit institutions, and unencumbered government securities. The denominator, tangible banking assets, is calculated or estimated as total assets minus goodwill and other intangibles.

We also assess a bank’s management of cash inflows and outflows and its ability to maintain a positive net funding gap over a 12-month horizon.

For finance companies, we assess an entity’s debt maturity coverage. We compare the stock of available, unrestricted, and unencumbered liquid assets and the amount of debt maturities arising over the next 12 months. We consider committed, unsecured bank lines with maturities exceeding one year as liquid resources. We also assess a finance company’s ability to generate cash flow relative to its debt level. We compute funds from operations using the amount of cash flow from operations before changes in operating assets and liabilities and excluding amounts related to loan originations and collections. In addition, we consider the ratio of secured debt to tangible assets. A lower ratio generally indicates a more stable funding structure.

Other factors to consider including diversification and reliability of market funding counterparties, funding support from affiliates, quality of unencumbered assets, ability to access market for new funding, the rigor of liquidity monitoring and control systems, as well as contingency planning and liquidity stress testing.

Securities firms in Vietnam are typically active in securities brokerage, margin lending, investment banking, market making and underwriting, and/or principal trading and investing. They often commit their own capital to act as principals in dealings with other market participants, and/or tend to be balance sheet intensive and have confidence-sensitive business models. Their funding structure tends to include a significant amount of confidence-sensitive, short-term funding. Many firms are subsidiaries of commercial banks in Vietnam. Unlike banks that are regulated by the State Bank of Vietnam, securities firms are regulated by State Securities Commission under the Ministry of Finance of Vietnam.

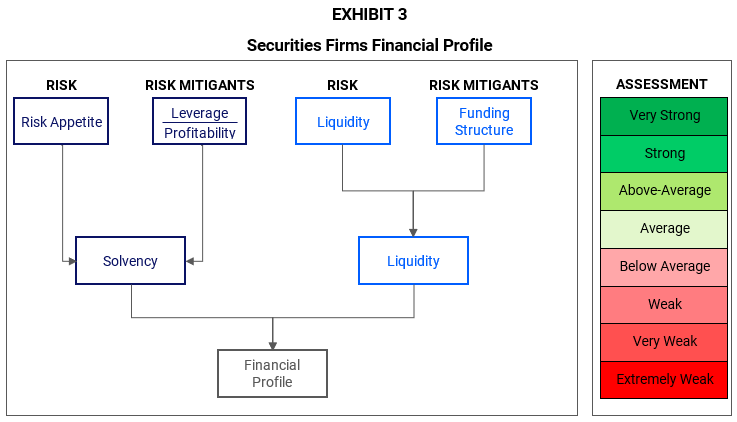

Our analysis of a securities firm’s financial profile incorporates key considerations on solvency and liquidity, which are important indicators of its exposure to risk and its capacity to absorb losses.

Source: VIS Rating

Solvency is indicated by a securities firm’s asset risk relative to its loss-absorbing capacity. Mitigants to asset risk are a firm’s capital and reserves, which are designed to absorb losses, and its earnings capacity.

Securities firms operate in confidence-sensitive and inherently complex markets that are prone to volatility and sudden changes in liquidity. Managing risk is a core attribute of securities firms, and firms that take on high levels of balance sheet risks may result in financial stresses that challenge its viability.

How We Assess It

We assess a firm’s risk appetite by comparing the stock of higher risk assets on- and off-balance sheet relative to its tangible assets. The lower the ratio, the lower is the inherent risk in the firm's assets and exposures, relative to the size of its balance sheet.

The numerator is the sum of the reported value of the firm’s higher risk securities and investments, and our measure of its exposure to off-balance sheet commitments and contingencies. The denominator, tangible assets, is total assets less goodwill & other intangible assets.

We will also look out for concentrations in highly volatile or illiquid investment securities, and/or excessive growth and exposure to market risks. Higher risk assets may include overdue margin loans, investments in securities that are subject to significant market risk, investments in unlisted equities and debt instruments that have little or no market activity and/or may be subject to substantial valuation haircuts upon disposal, large receivables from related parties, etc.

An assessment of balance sheet leverage provides an important gauge of the firm’s capacity to cope with loss of asset values and absorb losses and/or the firm’s vulnerability to market distortions that may cause confidence-sensitive counterparties to be concerned about its solvency. A firm’s capital structure can include equity and debt to finance its operations and growth. The higher the leverage ratio, the more the firm is leveraging its equity in pursuing its business activities. Excessively high leverage exposes firms to risks of magnified losses during market stress relative to its loss absorbing buffer.

How We Assess It

We assess a firm’s leverage ratio. The numerator is the firm’s tangible assets and off-balance sheet exposures including commitments and contingencies. The denominator is the firm’s tangible common equity.

The higher the real or perceived risk, the more capital an entity will need to maintain the confidence of creditors. A higher level of capital increases financial flexibility and allows an entity to finance growth and acquisitions, as well as protect bondholders against losses in times of stress.

Earnings strength reflects a securities firm’s ability to generate revenue and keep expenses in check, and thus generate capital. Strong and stable earnings will support capital generation to absorb losses and recover from shocks and thus its long-term viability. Conversely, volatile earnings can adversely affect market confidence.

The ability to generate capital internally from earnings on a consistent basis, manage variable expenses and successfully navigate the highs and lows of business cycles are important contributors to a firm’s relative credit strength.

How We Assess It

We measure a firm’s return on average total assets to assess its ability to generate a return on its core assets, its franchise strength and competitive position. We assess the volatility of a firm’s pre-tax earnings to determine the stability of its income streams throughout the cycle.

We use the firm’s pre-tax earnings coefficient of variation for the eight most recent semi-annual fiscal reporting periods. For ratios calculated on a historical basis, we use the most recent trailing eight periods. The pre-tax earnings coefficient of variation is the standard deviation of the market maker’s pre-tax earnings divided by the mean of its pre-tax earnings.

Because securities firms are inherently confidence-sensitive, a rapid loss of confidence from counterparties or clients can lead to a rapid loss of liquidity and funding for securities firms, resulting in insufficient resources to remain viable.

Being inherently confidence-sensitive, securities firms must have adequate available resources to support their daily business activities and their longer-term plans and overcome stress events. Inadequate available resources to cope with stress events can result in a rapid loss of confidence by counterparties or customers.

How We Assess It

We assess the ratio of liquidity inflows/outflows i.e., amount of available liquidity available on balance sheet and/or undrawn committed facilities to cope with a scenario that all funding sources of the securities firm become unavailable or are withdrawn and its off-balance sheet commitments crystalize.

Liquidity inflows include unrestricted cash, amounts due from other financial institutions, securities and investment portfolios, cash inflows from operating assets such as receivables from customers, brokers, etc., and available funding from undrawn, committed funding facilities. We may apply haircut rates to each item to assume loss in value in a stress scenario. Liquidity outflows include all short-term funding sources, cash outflows from operating liabilities, and off-balance sheet commitments and contingencies.

The higher the ratio of liquidity inflows/outflows, the better the firm is prepared to withstand a liquidity shock. Conversely, the lower the ratio, the more of a challenge the firm might face in surviving such a shock without any extraordinary external support.

Firms with adequate liquidity in general have a funding structure that is termed out relative to asset risk and other obligations.

How We Assess It

We assess a firm’s funding ratio by comparing its long-term funding structure with its long-term asset risk and other obligations. A high funding ratio indicates that the firm has superior ability to fund its long-term balance sheet and off-balance sheet commitments with long term funding sources – from borrowings, debt obligations and equity. It also indicates a firm’s low reliance on short term funding sources and low vulnerability to market stress and refinancing risks.

The numerator, long-term capital, includes total equity and long-term debt. The denominator, uses of long-term capital, includes amounts for haircut applied to securities and investments and receivables, other long-tern assets including intangibles and off-balance sheet exposures.

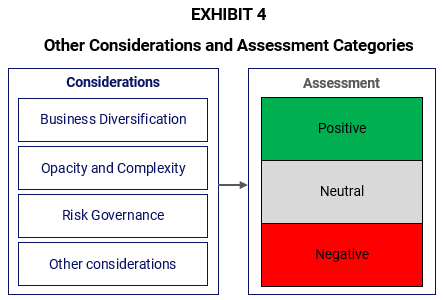

We may assess additional considerations that are not incorporated into the solvency and liquidity profiles of a bank and/or finance company and/or securities firm. Some of these considerations may be important to all financial institutions, while others may be important only under certain circumstances or for a subset of entities. Each consideration is assessed based on a three-category scale: Positive, Neutral and Negative. For entities with Positive assessments, we may incorporate positive adjustments to arrive at their credit ratings. Conversely, credit ratings of entities with Negative assessments may incorporate negative adjustments.

Source: VIS Rating

Following are some examples of additional considerations that may be reflected in credit ratings.

The composition of an entity’s business activities can be an important consideration in our assessment of an entity’s credit profile. An entity that is dependent on a single business may be more vulnerable to potential changes in market dynamics and at higher risk than a firm whose multiple lines of business help to insulate it from problems that arise from a single activity. We may also consider the entity’s geographical footprint and the economic diversity in the regions that it operates.

The riskiness of a financial institution increases with its opacity and complexity, other things being equal. We consider the extent to which an entity’s inherent organizational complexity may heighten management’s challenges and increase the risk of strategic and business errors, as well as operational errors.

Examples of complexity include operating numerous business lines across many legal entities, which may bring diversification benefits, but also create organizational and operational complexity; complex ownership or shareholding structures, etc.

Key personnel risk and an entity’s corporate governance structure, management and strategic execution provide important information about its risk profile. We may also consider the risks associated with an entity’s risk governance, underwriting controls, pricing sophistication, staffing and technology in the context of the lines of business. We also consider indications of a lack of quality in auditing and/or internal controls, related party transactions and the extent that risks may be mitigated or exacerbated by an entity's risk management policies or practices.

Environmental, social and governance (ESG) considerations may affect the credit quality of financial institutions in Vietnam and their borrowers. ESG issues typically have disproportionate downside risk. However, ESG considerations are not always negative, and they can be a source of credit strength in rare instances. For example, a bank or finance company that has outstandingly strong governance is more likely to have a management culture of full-degree risk assessment and informed decision-making with a view toward long-term sustainability.

A demonstrable financial track record can be instrumental in building customer and market trust, which creates franchise value and supports a bank’s or finance company’s performance during a down cycle. A track record of performance during various periods of the cycle is helpful in assessing an entity’s potential risk posture and credit quality. For entities that lack a financial history of at least several years, our projections may reflect more conservative expectations than management’s projections.

We rely on the accuracy of audited financial statements to assign and monitor credit ratings in this sector. Disclosure of relevant and timely financial information, and consistent application of financial information indicate a financial institution’s corporate governance and transparency as well as its compliance with company policies and regulatory standards; lapses in the above could indicate the opposite. Auditors’ reports and comments, unusual restatements of financial statements or delays in regulatory filings may indicate weaknesses in internal controls.

Financial Institutions in Vietnam are subject to varying degrees of regulatory oversight. We typically consider whether an entity complies with regulatory requirements and whether it is near to breaching any regulatory triggers, as well as the impact of those triggers. Additionally, regulations may entail limitations on an entity’s operations, which we will incorporate in our forward-looking assessment.

We recognize the possibility that an unexpected event could cause a sudden and sharp decline in an entity’s fundamental creditworthiness. Event risks — which are varied and tend to have low probability and high impact — can overwhelm even a stable, well-capitalized bank or finance company. Some types of event risks include mergers and acquisitions, spin-offs, litigation, pandemics, significant cyber-crime events and shareholder distributions.

In our assessment of support from affiliated entities, we typically consider both the creditworthiness of the support provider and its recipient, including the likelihood of failure of a financial institution, the capacity and willingness of its support provider to deliver support in a timely manner, and the extent to which the support provider and the supported financial institution are jointly susceptible to adverse circumstances that could weaken their financial position. We typically consider the support provider’s and supported entity’s respective operating environment. In addition, we typically assess whether the support provider’s actions may cause additional risk to creditors of the supported financial institution (e.g., requiring large distribution or upstream loans or guarantees).

Explicit support may be provided by the parent in the form of a direct guarantee that is usually intended to transfer the credit quality of the support provider to the supported entity. In assessing explicit support, we typically consider the specific legal nature and enforceability of the support as well as the likelihood of timely payment and its possible termination.

For implicit, non-legally binding support, we consider the support provider’s capacity to provide support, and its willingness to support. Our assessment of the benefit to a financial institution’s credit profile is primarily based on our assessment of the financial strength of the support provider, extent of strategic linkage and integration of business operations between the supported entity and its support provider, and/or past evidence of support. Conversely, we also consider the potential credit drag on the supported entity’s credit profile that may be due to an affiliation to a financially weak parent.

This component of our overall approach to assessing credit risk considers the effect of the failure of the financial institution — with support from affiliates having been either denied or exhausted — on its various debt classes, and the absence of any government support. We typically approximate the effect of the entity’s failure on different debt instruments by applying a notching approach to approximate the relative loss given failure and not necessarily its default.

The distinction reflects the potential that a government could intervene to bail out a bank or a group of creditors before a general default occurs. In our approach, we typically consider a security’s priority of claim in bankruptcy and its other structural features. Individual debt instrument ratings may be notched up or down from the issuer rating or the senior unsecured rating to reflect our view of the likely regulatory treatment of the issuer and its securities during failure and the issuer’s capital, and assessment of relative differences in expected loss related to an instrument’s seniority level and collateral.

Our analysis for holding companies considers structural subordination as well as the diversification or concentration of cash flows available to the holding from its subsidiaries and issuer-specific support arrangements.

Our approach to assessing government support for a financial institution is similar to assessing support from an affiliate. We incorporate the capacity and willingness of the support provider - government or public entity - to provide support in a timely manner and the dependence between the supported bank and the relevant government or public entity. We typically consider the government’s policies or regulatory framework, the financial institution’s role in financial markets, and the possible impact that a failure of the bank would have on the market.

Unlike banks, our ratings of finance companies and securities firms do not typically reflect an expectation of government support. Based on our observations, we believe government support would neither be widely offered nor sufficiently reliable nor predictable to be routinely incorporated into our ratings for finance companies and securities firms in Vietnam. In the exceptional cases where we believe such government support is meaningful and long term in nature, we apply the approach described in the preceding paragraph.

After assessing government support or intervention risk and its effect on the preliminary issuer-level and debt instrument-level assessments, we typically assign an issuer credit rating to the entity. We may also assign debt instrument- level credit ratings.

We may also assign short-term credit ratings. In cases where the issuer has sufficient intrinsic liquidity, we map short-term credit ratings from long-term credit ratings[3]. In cases where we consider intrinsic liquidity less than sufficient (for example, where intrinsic liquidity will not cover the next 12 months of maturing obligations and accessing credit markets may be difficult), the short-term credit rating may be lower than indicated by the mapping.

This credit rating methodology does not include an exhaustive description of all factors that we may consider in assigning credit ratings in this sector. Financial institutions may face new risks or new combinations of risks, and they may develop new strategies to mitigate risk. We seek to incorporate all material credit considerations in credit ratings and to take the most forward-looking perspective on the risks and mitigants where we have sufficient information and visibility.

Ratings reflect our expectations for a financial institution’s future performance; however, as the forward horizon lengthens, uncertainty increases, and the utility of precise estimates typically diminishes. In most cases, nearer-term risks are more meaningful to issuer credit profiles and thus have a more direct impact on ratings. However, in some cases our views of longer-term trends may have an impact on credit ratings.

The information used in assessing the factors and sub-factors is generally based on information provided by the company, including financial statement disclosures and publicly available data, such as disclosures by regulators. We may also incorporate non-public information.

While our credit ratings reflect both the likelihood of a default on contractually promised payments and the expected financial loss suffered in the event of default, the stand-alone assessment and LGF notching approach in this credit rating methodology is principally intended to capture fundamental characteristics that drive going-concern credit risk. As a debt instrument becomes impaired or defaults or is very likely to become impaired or to default, ratings typically include additional considerations that reflect our expectations for recovery of principal and interest, as well as the uncertainty around that expectation.

Our forward-looking opinions are based on assumptions that may prove, in hindsight, to have been incorrect. Reasons for this could include unanticipated changes in any of the following: the macroeconomic environment, general financial market conditions, industry competition, disruptive technology, or regulatory and legal actions. In any case, predicting the future is subject to substantial uncertainty.

[1] Credit rating methodologies describe the analytical framework that credit rating councils of VIS Rating use to assign credit ratings. Methodologies set out the key analytical factors that VIS Rating believes are the most important determinants of credit risk for the relevant sector. However, credit rating methodologies are not exhaustive treatments of all factors reflected in VIS Rating’s credit ratings.

[2] Refer to VIS Rating’s Rating Symbols and Definitions.

[3] Refer to VIS Rating’s Rating Symbols and Definitions.

When you visit any website, it may store or retrieve information on your browser, mostly in the form of cookies. This information might be about you, your preferences, or your device and is mostly used to make the site work as you expect it to. The information does not usually directly identify you, but it can give you a more personalized web experience. VIS Rating respects your right to privacy, you can choose not to allow some types of cookies.

Click on the different Cookies category headings to find out more and change our default settings. However, blocking some types of cookies may impact your experience of the site and the services we can offer.

Cookie Notice